Bill Harkins

The physical structure of the Universe is love. It draws together and unites; in uniting, it differentiates. Love is the core energy of evolution and its goal.”

~ Teilhard de Chardin, Human Energy

Last week Vicky and I enjoyed a visit to the Fernbank Science Museum with our younger son Andrew, daughter-in-law Margaret, and grandchildren Sophia and Georgie. We have always enjoyed our sojourns to Fernbank Don’t Miss This Ultimate Exhibit at Fernbank and have fond memories of taking both of our sons there when they were young, so the tradition continues!

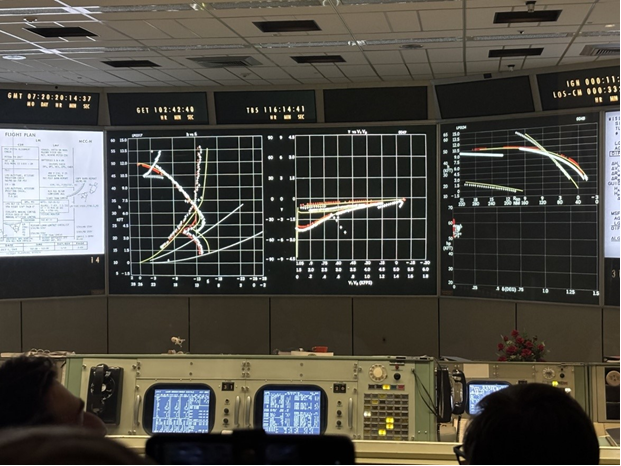

The week prior our older son Justin, and his family, Michelle, Alice, and Jack, who live in Montana, visited Andrew, Margaret and family in Houston, where Andrew is an oncology fellow at MD Anderson They visited the NASA space center there and saw the “mission control” center where so much history has been made…”Houston, we have a problem.”

We hoped our children would develop a sense of wonder in the natural world and an interest in science, and now we delight in spending time with our grandchildren in these contexts as well!

In 1982 I enrolled at Vanderbilt Divinity School on a trial year Lily Foundation scholarship. Vicky and I journeyed to Nashville primarily for her to work on a Master’s in Behavioral Health Nursing, while I considered resuming my interest in neuroscience upon our eventual return to Atlanta, where I had been working in the Neuroendocrinology Research Lab at GMHI. Instead, we remained at Vanderbilt for doctoral work in psychology and religion. It is among my intellectual and spiritual homes. At the time there were over 40 faith traditions represented at Vanderbilt, and I delighted in the learning that accrued among so many different perspectives! Interaction and interdisciplinary learning between the departments of psychology, philosophy, and religion was robust, and this, too, created a wonderful milieu for learning.

One of my favorite professors was Dr. John Compton, who taught courses in philosophy of science, and the intersection of science and religion. He was a brilliant teacher whose father, Arthur Compton, was a Nobel Laureate who worked on the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos, New Mexico, where John attended High School. John encouraged us to engage in the dialogue between science and religion, ask tough questions, and enjoy the ambiguous spaces between the Hegelian dialectic of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. We read Thomas Kuhn’s book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962) which challenged the view of scientific discovery in which progress is generated and accelerated by a particular great scientist. Rather, Kuhn suggested, new discoveries depend on shared theoretical beliefs, values, and techniques of the larger scientific community—what he called the “disciplinary matrix” or “paradigm.” Several years ago, we journeyed to Santa Fe and Los Alamos to run the Jemez Mountain Trail Races…

…and we visited the museum in Los Alamos where Arthur Compton and colleagues worked on the Manhattan Project Bradbury Science Museum | Los Alamos National Laboratory

Building upon this idea of the disciplinary matrix, scholars identified attitudes towards gender and race as among those shared values and beliefs and suggested that we need in order to question the way in which histories of science recount who does what, and who gets credit. Evelyn Fox Keller, writing in her book Reflections on Gender and Science, suggested that science is neither as impersonal nor as cognitive as we thought. And it is not reserved for male geniuses working on their own. It occurs through collaboration. This includes religious values, critical inquiry, and dialogue. Collaboration is also a key component of “emotional intelligence,” defined as the ability to manage both your own emotions and anxiety and understand the emotions of people around you.

There are five key elements to Emotional Intelligence: self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy, and social skills. People with high EI can identify how they are feeling, what those feelings mean, and how those emotions impact their behavior and in turn, other people. It’s a little harder to “manage” the emotions of other people – you can’t control how someone else feels or behaves. But if you can identify the emotions behind their behavior, you’ll have a better understanding of where they come from and how to best interact with them. This, too, is ultimately about a collaborative spirit, and openness to a sense of wonder. It can save us from micromanaging narratives that, ultimately, we cannot control, and allow us to co-create contexts for growth, and new paradigms of hope, wonder, and shared learning.

High Emotional Intelligence overlaps with strong interpersonal skills, especially in the areas of conflict management and communication – crucial skills in the workplace, and especially important for scientific discovery and organizations during times of transition!

The year Kuhn’s text was published, the Mercury Friendship 7 mission occurred. John Glenn, piloting the spacecraft, was returning to earth when the automatic control system failed, forcing him to manually navigate the capsule to touchdown. Katherine Johnson, one of the (“Hidden Figures”) African American mathematicians working for NASA, calculated and graphed Glenn’s reentry trajectory in real time, accounted for all possible complications, and traced the exact path that Glenn needed to follow to safely splash down in the Atlantic.

Such stories amplify and deepen the work of Kuhn, Keller, and others who encourage us to create a future in which more and different people—regardless of race, gender, religion, class, or sexual identity—can imagine themselves as participants in new unfolding discoveries and creating new possibilities during times of change. This includes our church communities as well! Much is changing, of course, in mainline Protestantism and in our own denomination, and at Holy Family too! A collaborative, lay-led and clergy supported paradigm can assist us as we find our way in this new season.

At heart, these narratives evoke the relationality of Creation, and God’s love, an evolving, divine, dynamic energy. As the poet Wallace Stevens said, “Nothing is itself taken alone. Things are because of interrelations or interactions.”

And as Ilia Delio has written, “If being is intrinsically relational (as the Trinity evokes) then nothing exists independently or autonomously. Rather, “to be” is “to be with” …I do not exist in order that I may possess; rather, I exist in order that I may give of myself, for it is in giving that I am myself.”[I]

Or, as Mary Oliver said so well,

“And what do I risk to tell you this, which is all I know?

Love yourself. Then forget it. Then, love the world.”

Sounds like a relational, collaborative, Trinitarian Gospel to me, and during this season of Lent, this might be an especially important component of our Lenten discipline and discernment! Let’s be open to wonder, and hope, and imagination as we view the world around us, and not allow old narratives or anxieties keep us in bondage. Let’s covenant to cultivate wonder and give of ourselves as Delio implores us to do! Paying attention in those threshold, liminal spaces where the world awaits us is a sacred task indeed! After all, as Teilhard said so well, “Love is the core energy of evolution, and its goal.”

Friends, this will be my final episode of Notes from the Trail as I transition out of my role as interim, and as we prepare to welcome its new rector. I pray blessings upon you all, and I give a deep bow of gratitude for the honor of having served this past year. Godspeed, and I’ll catch you later down the trail! Bill+

[i] Ilia Delio, The Unbearable Wholeness of Being: God, Evolution, and the Power of Love (2013), Orbis Books